General information

|

Production seasons

|

Write-up taken from the IRRI's Rice Almanac (2013):

The Japanese islands lie off the eastern coast of Asia, roughly in a crescent shape. The country consists of four main islands with about 4,000 smaller ones. The northern limit of rice cultivation is 44° N. Rice is grown up to 1,400 m altitude in the central region of the main island.

The climate is humid temperate and oceanic with four distinct seasons. Rainfall during the rainy season in June and July is indispensable to rice cultivation. The temperature and solar radiation from April to October are ideal for rice growing.

The country’s population in 2010 was nearly 127 million with a density of 337 per km2. The agricultural population declined from about 29 million in 1960 to about 3 million in 2010 due to diversification of the economy and very slow population growth during recent decades. The country’s population grew at barely 0.02% per year in 2005-10.

Japan has few natural resources; its industrial sector greatly depends on imported raw materials and fuel. The economy is technologically developed and very efficient in foreign trade. In 2010, 73.8% of the country’s GDP came from the service sector; the industrial sector contributed 24.8% whereas agriculture contributed only 1.2%.

Recent developments in the rice sector

Japan continues to be self-sufficient in rice. Rice remains important and is embedded in Japanese culture. With the shift in people’s diet, rice consumption has fallen since the 1970s. Annual per capita rice consumption declined from 63 kg in 1995 to 54 kg in 2009. Consequently, per capita caloric intake from rice fell from 23.1% (675 kcal) per day in 1995 to 21.3% (581 kcal) per day in 2009, while the share of wheat rose slightly from 12.3% per day in 1995 to 14.2% per day in 2009. In parallel, per capita protein intake from rice declined from 12.3% per day in 1995 to 11.5% per day in 2009, whereas wheat accounted for 10.0% per day in 1995 and 11.9% per day in 2009.

The small agricultural sector is heavily subsidized and protected. The rice sector is supported by high prices paid by consumers that allow many farm households to maintain small farms. The government controls trade through a tariff quota, with a high tariff on imports outside the quota. The country has a crop diversion (or rice area reduction) program wherein farmers are paid to substitute rice with other crops (e.g., wheat, soybean) or let the land remain fallow, so that the rice supply will not exceed demand at market price levels.

Because of the government’s restrictions on rice area, the area harvested to rice fell from 2.1 million ha in 1995 to 1.6 million ha in 2010; this contraction amounted to 1.1% per year in 2005-10. Rice yield grew by only about 0.2% per year in 2005-10. The mean rice yield in 2010 was 6.5 t/ha, very close to the 6.3 t/ha harvested in 1995. The overall result was a 1% per year fall in rice production in 2005-10.

Japan’s rice exports improved slightly from 10,000 t in 1995 to 38,000 t in 2010. Under the auspices of the World Trade Organization (WTO), Japan allows market access to imported rice of 8% of the country’s rice requirement. Hence, rice imports increased from 30,000 t in 1995 to 660,000 t in 2010. Most of these rice imports, however, are not released directly to the domestic market but are placed into government stocks and later used in the form of aid to developing countries or sold as an input to food processors.

Below are some of the major policies of the Japanese government that directly affect the rice economy:

- For decades, Japan pursued the goal of food self-sufficiency by using a number of commodity programs such as a producers’ quota, income stabilization policies, deficiency payments, and rice diversion programs.

- To revitalize the agricultural sector, younger segments of the population are encouraged to take up farming activities through incentives.

- The New Food, Agriculture, and Rural Areas Basic Plan, developed in March 2010, is a major change in agricultural policy to swiftly renew and revitalize food and communities. This plan sets 50% as the target for the food self-sufficiency ratio on a supplied calorie basis and 70% on a production output basis to be achieved in 2020. This policy provides government subsidies to support farmers whose main agricultural products are rice and other cereals at a level depending on certain production targets that are decided by prefectural and city governments and municipalities based on a food self-sufficiency target rate. The subsidies are calculated based on the difference between the nationwide average production cost and the nationwide average retail price. Every farmer participating in this scheme has been given a basic subsidy of 1 million yen per hectare.

Rice environments

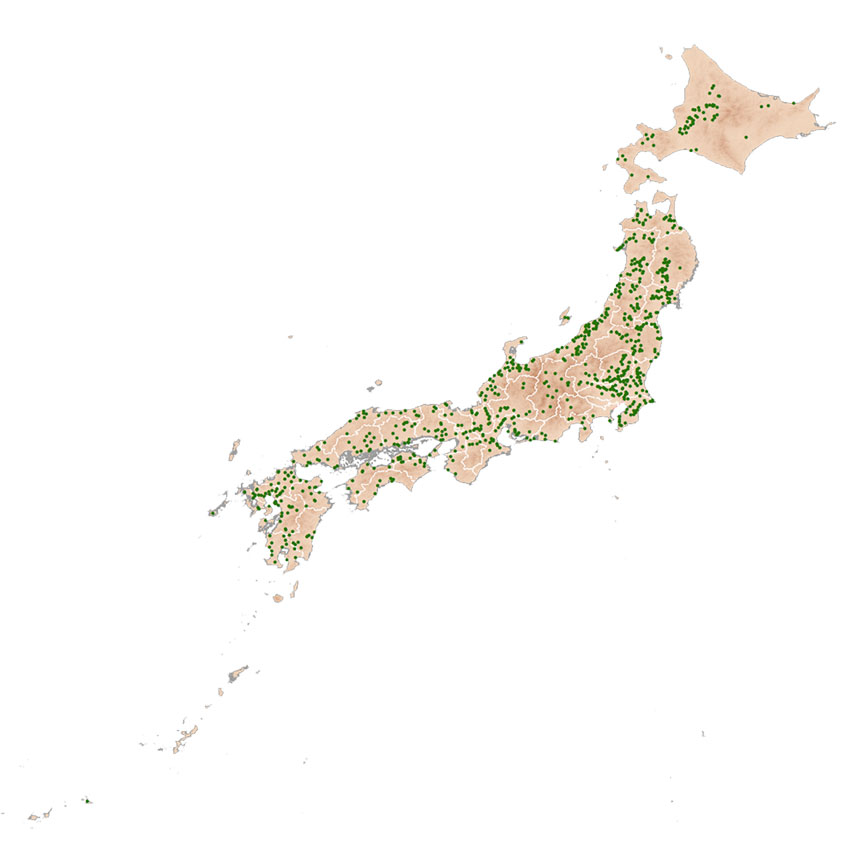

Rice ecosystems in Japan cover an extensive range of latitudes, including subtropical, temperate, and subfrigid areas. Most rice fields are on the plains of the major river basins. Many are also located in terraces and valleys.

Japan’s rice culture is characterized by cultivation in the higher latitudes. To handle the cold weather in the northern part of the country, early-maturing cold-tolerant varieties were developed. Rice cultivation in the cold area is based on good-quality older seedlings for early transplanting, deepwater irrigation to protect crops from low night temperature, windbreak nets, and the application of organic matter to improve soil fertility.

Rice is grown under irrigated conditions. Japanese paddies feature concrete irrigation ditches largely constructed as public works projects. Many paddies have underground drainage systems that allow water to drain into the canals during the off-season. These paddies are easy to manage but can affect wildlife.

Nearly 85% of the 2.3 million farms in Japan cultivate rice. Farming is highly mechanized. Average landholding is very small, about 0.8 ha. Most farmers with smaller farm size consider rice farming a part-time job.

Japan’s northernmost island, Hokkaido, is the country’s leading rice producer. Also, the broad coastal plain of Shonai near the Sea of Japan has plenty of water and nutrient-rich soil and is considered to be one of Japan’s most fertile granaries.

Improved varieties of japonica rice are planted in most of the prefectures or regions in the country. The popularity of a rice variety in the country depends on its taste. Hokkaido’s Yumepirika variety and Niigata’s Koshihikari are popularly known for their palatability and command a premium price in the market.

Rice production constraints

Japan has an aging population and very low population growth, which could result in labor shortages and will likely constrain future rice production. Many rice fields are being abandoned after the owners die or become too old to cultivate them. With the changing level of education, rice farming is not attracting the younger generation. As of April 2010, 23% of the population was aged 65 or older. Projections made in 2006 indicated that the population of 127 million would decline to 90 million by 2055, when 41% of the population would be 65 or older.

Rice farmers are often also engaged in nonagricultural employment due to the small size of landholdings used for rice farming.

Because of global warming, high summer temperature and erratic rainfall are reducing yields. Some farmers are trying heat-resistant varieties but their taste is significantly different. Some experts say that it may take many years for consumers to accept heat-resistant, high-yielding varieties.

In spite of substantial farm subsidies and price support provided by the government, rice farming cannot compete with other economic activities, and income from it is lower than from nonagricultural earnings. Despite mechanization, production costs are many times higher than in tropical Asia because of exorbitant land prices and the high opportunity cost of farm labor.

Rice production opportunities

Japanese rice research will also help solve problems in neighboring low-income rice-growing countries of South and Southeast Asia, while regional research by IRRI and partners will benefit Japanese rice farming also. Reducing production cost, increasing productivity through the application of advanced technology, and multipurpose use of rice fields in agriculture are important for sustaining rice cultivation in Japan.

Using rice as alternative flour in making bread and noodles can stimulate demand for rice. The potential of rice as poultry and livestock feed can also help increase the demand for rice and hence more farmers would be encouraged to engage in rice farming. As a result, the country would maintain its self-sufficiency in rice and attain food self-sufficiency as well. The government can export rice in excess of domestic demand to other countries that have a shortfall in rice production.

The population projections suggest that the government may have to consider immigration as a solution to unbalanced worker-retiree ratios to augment the possible labor shortages in coming years. Rice farming would benefit from strategies to encourage working couples to have children.

Source: FAO’s FAOSTAT database online and AQUASTAT database online, as of September 2012.